Rosin

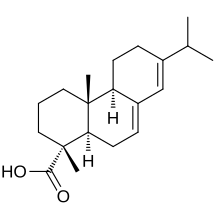

Rosin (/ˈrɒzɪn/), also known as colophony or Greek pitch (Latin: pix graeca), is a resinous material obtained from pine trees and other plants, mostly conifers. The primary components of rosin are diterpenoids, i.e., C20 carboxylic acids. Rosin consists mainly of resin acids, especially abietic acid.[1] Rosin often appears as a semi-transparent, brittle substance that ranges in color from yellow to black and melts at stove-top temperatures.

In addition to industrial applications such in as varnishes, adhesives, and sealing wax, rosin is used with string instruments on the bow hair to enhance its ability to grip and sound the strings, and it provides grip in various sports and activities. Rosin also serves as an ingredient in medicinal and pharmaceutical formulations and can cause contact dermatitis or occupational asthma in sensitive individuals. It is an FDA approved food additive.[2]

The name "colophony" originates from colophonia resina, Latin for "resin from Colophon" (Ancient Greek: Κολοφωνία ῥητίνη, romanized: Kolophōnía rhētínē),[3][4] an ancient Ionic city.[5]

Properties

[edit]

Rosin is brittle and friable, with a faint pine odor. It is typically a glassy solid, though some rosins will crystallize, especially when brought into solution.[6] The practical melting point is variable, some being semi-fluid at the temperature of boiling water, others melting at 100 to 120 °C (212 to 248 °F). It is flammable, burning with a smoky flame. It is soluble in alcohol, ether, benzene and chloroform.

Rosin, consisting mainly of abietic acid, combines with caustic alkalis to form salts (rosinates or pinates) that are known as rosin soaps. They are uses in soap making.

Uses

[edit]

Rosin is the principal component has been used for centuries as a flux for soldering. (Abietic acid in the flux removes oxidation from the surfaces of metals, increasing their ability to bond with the liquified solder.)

Rosin, of which abietic acid is the principal component has been used for centuries as a flux for soldering. (Abietic acid in the flux removes oxidation from the surfaces of metals, increasing their ability to bond with the liquified solder.)

- Is rubbed on the hair of a violin bow to increase friction.

- Has been used for centuries for caulking ships.[8]

- Is approved by the US FDA as a miscellaneous food additive.[7]

Rosin is an ingredient in printing inks, photocopying and laser printing paper, varnishes, adhesives (glues), soap, paper sizing, soda, soldering fluxes, and sealing wax.

Rosin can be used as a glazing agent in medicines and chewing gum. It is denoted by E number E915. A related glycerol ester (E445) can be used as an emulsifier in soft drinks. In pharmaceuticals, rosin forms an ingredient in several plasters and ointments.

In industry, rosin is a flux used in soldering. The lead-tin solder commonly used in electronics has 1 to 2% rosin by weight as a flux core, helping the molten metal flow and making a better connection by reducing the refractory solid oxide layer formed at the surface back to metal. It is frequently seen as a burnt or clear residue around new soldering.

Rosin is also sometimes used as internal reinforcement for very thin skinned metal objects - like silver, copper or tin plate candlesticks, or sculptures, where it is simply melted, poured into a hollow thin-skinned object, and left to harden.

A mixture of pitch and rosin is used to make a surface against which glass is polished when making optical components such as lenses.

Rosin is added in small quantities to traditional linseed oil/sand gap fillers ("mastic"), used in building work.

When mixed with waxes and oils, rosin is the main ingredient of mystic smoke, a gum which, when rubbed and suddenly stretched, appears to produce puffs of smoke from the fingertips.

Rosin is extensively used for its friction-increasing capacity in several fields:

- Ballet, flamenco, and Irish dancers are known to rub the tips and heels of their shoes in powdered rosin to reduce slippage on clean wooden dance floors or competition/performance stages. It was at one time used in the same way in fencing and is still used as such by boxers.

- Gymnasts and team handball players use it to improve grip. Rock climbers have used it in some locations.

- Olympic weightlifters rub the soles of their weightlifting boots in rosin to improve traction on the platform.

- It is applied to the track surface at the starting line of drag racing courses to improve traction.[citation needed]

- Bull riders rub rosin on their rope and glove for additional grip.

- Baseball pitchers and ten-pin bowlers may use a small cloth bag of powdered rosin for better ball control. Baseball players sometimes combine rosin with sunscreen, creating a very sticky substance that allows far more grip on the ball than the rosin alone will; the use of such a substance is a violation of Major League Baseball rules.

- Rosin can be applied to the hands in aerial acrobatics such as aerial silks and pole dancing to increase grip.

Other uses that are not based on friction:

- Fine art uses rosin for tempera emulsions and as painting-medium component for oil paintings. It is soluble in oil of turpentine and turpentine substitute, and needs to be warmed.

- In a printmaking technique, aquatint rosin is used on the etching plate in order to create surfaces in gray tones.

- In archery, when a new bowstring is being made or waxed for maintenance purposes, rosin may be present in the wax mixture. This provides an amount of tackiness to the string to hold its constituent strands together and reduce wear and fraying.[citation needed]

- Dog groomers use powdered rosin to aid in removal of excess hair from deep in the ear canal by giving the groomer a better grip to grasp the hairs with.

- Some brands of fly paper use a solution of rosin and rubber as the adhesive.

- Rosin is sometimes used as an ingredient in dubbing wax used in fly tying.

- Rosin is used hot to de-encapsulate epoxy integrated circuits.[9]

- Rosin can be mixed with beeswax and a small amount of linseed oil to affix reeds to reed blocks in accordions.

- Rosin potatoes can be cooked by dropping potatoes into boiling rosin and cooking until they float to the surface.[10]

Rosin and its derivatives also exhibit wide-ranging pharmaceutical applications. Rosin derivatives show excellent film forming and coating properties.[11] They are also used for tablet film and enteric coating purpose. Rosins have also been used to formulate microcapsules and nanoparticles.[12][13]

Glycerol, sorbitol, and mannitol esters of rosin are used as chewing gum bases for medicinal applications. The degradation and biocompatibility of rosin and rosin-based biomaterials has been examined in vitro and ex vivo.

Rosin soaps and esters

[edit]Treatment of rosin with sodium hydroxide or sodium carbonate converts the abietic acid into its sodium salt, which is known as a soap. Whereas most domestic soaps are sodium salts of straight-chain fatty acids, the rosin soaps have the branched and cyclic backbone associated with abietic acid. Rosin soaps, also called rosinates, are used to "size" paper, a process that gives paper a desirable hydrophobic texture.[1]

The conversion of abietic acid to esters is also practiced commercially. Ester of glycerol and methanol are both of interest. These materials are colorless syrups. They are compounded with polymers as tackifiers.[1]

Violin rosin

[edit]

Players of bowed string instruments rub cakes or blocks of rosin on their bow hair so it can grip the strings and make them "speak", or vibrate clearly.[14] Occasionally, substances such as beeswax, gold, silver, tin, or meteoric iron[15] are added to the rosin to modify its stiction/friction properties and the tone that can be produced.[16] Powdered rosin can be applied to new hair, for example with a felt pad or cloth, to reduce the time taken in getting sufficient rosin onto the hair. Rosin is often reapplied immediately before playing the instrument. Lighter rosin is generally preferred for violins and violas, and in high-humidity climates, while darker rosins are preferred for cellos, and for players in cool, dry areas.[17] There are also specific, distinguishing types for basses.

- Violin rosin can be applied to the bridges in other musical instruments, such as the banjo and banjolele, in order to prevent the bridge from moving during vigorous playing.

The type of rosin used with bowed string instruments is determined by the diameter of the strings. Generally this means that the larger the instrument is, the softer the rosin should be. For instance, double bass rosin is generally soft enough to be pliable with slow movements. A cake of bass rosin left in a single position for several months will show evidence of flow, especially in warmer weather.

Production

[edit]Three methods are used to collect rosin. Rosin exudates are collected from gashes in the bark of living pine trees. Alternatively (see below) rosin is extracted from stumps. Yet another source is pulp mills that use the Kraft process. Tall oil rosin is produced during the distillation of crude tall oil, a by-product of the kraft paper making process. The collection and processing of rosin is called Naval Stores.[1]

The separation of the oleo-resin into the essential oil (spirit of turpentine) and common rosin is accomplished by distillation in large copper stills. The essential oil is carried off at a temperature of between 100 °C (212 °F)° and 160 °C (320 °F), leaving fluid rosin, which is run off through a tap at the bottom of the still, and purified by passing through straining wadding. Rosin varies in color, according to the age of the tree from which the turpentine is drawn and the degree of heat applied in distillation, from an opaque, almost pitch-black substance through grades of brown and yellow to an almost perfectly transparent colorless glassy mass. The commercial grades are numerous, ranging by letters from A (the darkest) to N (extra pale), superior to which are W (window glass) and WW (water-white) varieties, the latter having about three times the value of the common qualities.

When pine trees are harvested "the resinous portions of fallen or felled trees like longleaf and slash pines, when allowed to remain upon the ground, resist decay indefinitely."[18] This "stump waste", through the use of destructive distillation or solvent processes, can be used to obtain rosin. This type of rosin is typically called wood rosin.

Because the turpentine and pine oil from destructive distillation "become somewhat contaminated with other distillation products",[18] solvent processes are commonly used. In this process, stumps and roots are chipped and soaked in the light end of the heavy naphtha fraction (boiling between 90 and 115 °C (194 and 239 °F)). Multi-stage counter-current extraction is commonly used. In this process, fresh naphtha first contacts wood leached in intermediate stages, and naphtha laden with rosin from intermediate stages contacts unleached wood before vacuum distillation to recover naphtha from the rosin, along with fatty acids, turpentine, and other constituents later separated through steam distillation. Leached wood is steamed for additional naphtha recovery prior to burning for energy recovery.[19] After the solvent has been recovered, "the terpene oils are separated by fractional distillation and recovered mainly as refined turpentine, dipentene, and pine oil. The nonvolatile residue from the extract is wood rosin of rather dark color. Upgrading of the rosin is carried out by clarification methods that generally may include bed-filtering or furfural-treatment of rosin-solvent solution."[18]

On a large scale, rosin is treated by destructive distillation for the production of rosin spirit, pinoline and rosin oil. The last enters into the composition of some of the solid lubricating greases, and is also used as an adulterant of other oils.

Locales

[edit]The chief region of rosin production includes Indonesia, southern China (such as Guangdong, Guangxi, Fujian, Yunnan and Jiangxi), and the northern part of Vietnam. Chinese rosin is obtained mainly from the turpentine of Masson's pine Pinus massoniana and slash pine P. elliottii.[citation needed] The latter species is native to the southeastern U.S., but is now widely planted in tree plantations in China.

The South Atlantic and eastern Gulf states of the United States is a second chief region of production. American rosin is obtained from the turpentine of longleaf pine Pinus palustris and loblolly pine P. taeda. In Mexico, most of the rosin is derived from live tapping of several species of pine trees, but mostly Pinus oocarpa, Pinus leiophylla, Pinus devoniana and Pinus montezumae. Most production is concentrated in the west-central state of Michoacán.[citation needed]

The main source of supply in Europe is the French district of Landes, in the departments of Gironde and Landes, where the maritime pine P. pinaster is extensively cultivated. In the north of Europe, rosin is obtained from the Scots pine P. sylvestris, and throughout European countries local supplies are obtained from other species of pine, with Aleppo pine P. halepensis being particularly important in the Mediterranean region.[citation needed]

Health effects

[edit]The fumes released during soldering have been cited as a causative agent of occupational asthma. The symptoms also include desquamation of bronchial epithelium.[20]

Prolonged exposure to rosin fumes released during soldering can cause occupational asthma (formerly called colophony disease[21] in this context) in sensitive individuals, although it is not known which component of the fumes causes the problem.[22]

Prolonged exposure to rosin, by handling rosin-coated products, such as laser printer or photocopying paper, can give rise to a form of industrial contact dermatitis.[23]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ a b c d Fiebach, Klemens; Grimm, Dieter (2000). "Resins, Natural". Ullmann's Encyclopedia of Industrial Chemistry. doi:10.1002/14356007.a23_073. ISBN 978-3-527-30673-2.

- ^ Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied (2022-08-25). "Food Additive Status List". FDA.

- ^ Colophon. Charlton T. Lewis and Charles Short. A Latin Dictionary on Perseus Project.

- ^ Κολοφώνιος. Liddell, Henry George; Scott, Robert; A Greek–English Lexicon at the Perseus Project.

- ^ "colophony". Oxford English Dictionary (Online ed.). Oxford University Press. (Subscription or participating institution membership required.) "ad. L. colophōnia (Pliny) for Colophōnia rēsīna resin of Colophon".

- ^ Palkin, S.; Smith, W. C. (1938). "A new non-crystallizing gum rosin". Oil & Soap. 15 (5): 120–122. doi:10.1007/BF02639482. S2CID 94421680.

- ^ a b Nutrition, Center for Food Safety and Applied (2022-08-25). "Food Additive Status List". FDA.

- ^ Hoiberg, Dale H., ed. (2010). "abietic acid". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. I: A-ak Bayes (15th ed.). Chicago, Illinois: Encyclopædia Britannica Inc. pp. 32. ISBN 978-1-59339-837-8.

- ^ Peter Laackmann, Marcus Janke (Dec 28, 2014). "Peter Laackmann, Marcus Janke: Uncaging Microchips (from 30:18-32:15)". YouTube. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved Feb 18, 2016.

- ^ "The Almost Lost Art of Rosin Potatoes". 6 December 2017. Archived from the original on 15 January 2019. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- ^ Satturwar, Prashant M.; Fulzele, Suniket V.; Dorle, Avinash K. (2005). "Evaluation of polymerized rosin for the formulation and development of transdermal drug delivery system: A technical note". AAPS PharmSciTech. 6 (4): E649 – E654. doi:10.1208/pt060481. PMC 2750614. PMID 16408867.

- ^ Lee, Chang-Moon; Lim, Seung; Kim, Gwang-Yun; Kim, Dong-Woon; Rhee, Joon Haeng; Lee, Ki-Young (2005). "Rosin Nanoparticles as a Drug Delivery Carrier for the Controlled Release of Hydrocortisone". Biotechnology Letters. 27 (19): 1487–90. doi:10.1007/s10529-005-1316-x. PMID 16231221. S2CID 24729281.

- ^ Fulzele, S. V.; Satturwar, P. M.; Kasliwal, R. H.; Dorle, A. K. (2004). "Preparation and evaluation of microcapsules using polymerized rosin as a novel wall forming material". Journal of Microencapsulation. 21 (1): 83–89. doi:10.1080/02652040410001653768. PMID 14718188. S2CID 24929166.

- ^ Mantel, Gerhard (1995). "Problems of Sound Production: How to Make a String Speak". Cello Technique: Principles and Forms of Movement. Indiana University Press. pp. 135–41. ISBN 978-0-253-21005-0.

- ^ "Larica metal rosin". 2009. Archived from the original on June 27, 2015. Retrieved Jun 15, 2014.

- ^ "All Things Strings:Rosin". 1 May 2010. Archived from the original on 1 May 2010.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Heather K. Scott (January 5, 2004). "The Differences Between Dark and Amber Rosin". Archived from the original on November 26, 2016. Retrieved Dec 27, 2016.

- ^ a b c Beglinger, E. (May 1958). "Distillation of Resinous Wood" (PDF). United States Department of Agriculture Forest Service. 496. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2014-01-07.

- ^ Kent pp.571&572

- ^ Meehan-Atrash, Jiries; Strongin, Robert M. (2020-07-01). "Pine rosin identified as a toxic cannabis extract adulterant". Forensic Science International. 312: 110301. doi:10.1016/j.forsciint.2020.110301. ISSN 0379-0738. PMC 7426011. PMID 32460222.

- ^ ""colophony disease", Archaic Medical Terms List, Occupational, on Antiquus Morbus website". Archived from the original on 2011-09-03. Retrieved 2007-03-13.

- ^ Controlling health risks from rosin (colophony) based solder fluxes, IND(G)249L, United Kingdom Health and Safety Executive, 1997 (online PDF) Archived 2011-01-12 at the Wayback Machine ISBN 0-7176-1383-6

- ^ "Rosin allergy - DermNet New Zealand". www.dermnet.org.nz. Archived from the original on 2013-02-09. Retrieved 2010-02-13.

References

[edit]- Kent, James A. Riegel's Handbook of Industrial Chemistry (Eighth Edition). Van Nostrand Reinhold Company (1983). ISBN 0-442-20164-8.

External links

[edit]- Kotapish, Paul (November–December 2001). "Sticky Business: How Rosin Is Made". Strings.